As railroads reached outlying villages and the countryside around Philadelphia during the nineteenth century, railroad companies and other enterprising real estate developers created fashionable residential enclaves, new suburban towns, and vast semirural estates. These developments enabled prosperous Philadelphians to live apart from the city while still enjoying its amenities and maintaining their positions in the urban industries, businesses, and professions that produced their wealth. In the new railroad suburbs, local shopkeepers and service workers also helped sustain semirural living for the upper and middle classes. Although automobiles later changed commuting habits, the railroads and the suburbs that developed around their stations established a geography and social order that in many ways persisted into the twenty-first century.

Residents of the recently developed railroad suburbs built their homes in fashionable architectural styles to showcase their wealth. Merchant Ebenezer Maxwell built this Gothic Revival home, which still stands on West Tulpehocken Street, in 1859. (Library of Congress)

The region’s first railroad suburbs developed along the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad (the PGN), which introduced commuter trains running northwest from the city in 1832. Using steam locomotives, the PGN operated frequent passenger service along essentially the same routes later served by SEPTA’s Chestnut Hill East and Norristown regional rail lines. The commuter trains made Germantown, founded in 1683, a suburb connected with Philadelphia long before its consolidation into the city in 1854. By the late 1850s, in addition to its stock of colonial-era homes Germantown had a cluster of suburban villas in the neighborhood of West Walnut Lane and Greene and West Tulpehocken Streets. Farther northwest, a few commuters from Chestnut Hill connected to the PGN by stagecoach or carriage during the 1830s and 1840s, but after 1854 they could ride the new Chestnut Hill Railroad to Germantown. The construction of a new Episcopal Church, St. Paul’s (built 1856-61), signaled Chestnut Hill’s increasing status as a suburb for the elite.

As railroad commuting expanded during the later decades of the nineteenth century, it produced social and geographic segregation as upper and middle class families sought distance from the intensifying industrialization and high rates of immigration in Philadelphia and other American cities. The cost of rail fares initially put daily commuting by train out of reach for all but the wealthiest riders, while local streetcars and (later) buses remained the affordable options for others. Because rail fares varied by distance, inner suburbs like Germantown had more middle-class commuters than more distant, semirural idylls of the elite. Steam trains did not appeal to many middle-class commuters to Philadelphia because the locations of terminals on the periphery of the business district required an additional long walk or streetcar ride to get to work. Streetcars running into the central city from closer, newly developing areas of North and West Philadelphia offered more-direct access, as did the Delaware River ferries that connected with railroads serving South Jersey. This did not change until late in the nineteenth century, when the two major rail systems serving the city relocated their main facilities to Center City (the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Broad Street Station, built 1879-82, and the Reading Terminal, built 1891-93).

Similar Patterns Elsewhere

The development of railroad suburbs in the Philadelphia region resembled patterns of metropolitan expansion occurring around the same time along railroad lines radiating from other major cities, including New York, Boston, and Chicago. During the 1850s, other Philadelphia-area railroads joined the PGN in offering commuter train services. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad started publishing housing guides for its line through Delaware County, and the West Chester and Philadelphia touted its route for commuters between its namesake communities. In southern New Jersey, the Camden and Atlantic Railroad, which began service in 1854, led to residential growth in Haddonfield, and a group of Philadelphia merchants acquired land and developed Merchantville after the arrival of the Camden and Burlington Railroad in 1867-68. From these South Jersey suburbs, commuters traveled by rail to Camden and then crossed by ferry to the commercial center of Philadelphia east of Sixth Street.

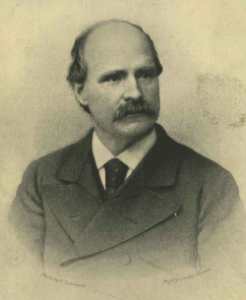

Banker Anthony J. Drexel, shown here in the late nineteenth century, planned the suburb of Wayne, Pennsylvania, in collaboration with George W. Childs, his co-owner at the Philadelphia Public Ledger. Downtown Wayne centers on an 1884 Pennsylvania Railroad Main Line station, served in the twenty-first century by the SEPTA Paoli/Thorndale line. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

By the 1870s and 1880s, a period of transition for the railroads, some lines had few commuter trains but on others the service became quite intensive. For example, in 1876, the Chestnut Hill Branch of the Philadelphia & Reading (successor to the PGN) offered thirty daily round trips between Center City and Germantown and encouraged daily commuting by offering special low-fare trains. During the 1870s, the Pennsylvania Railroad created havens for the elite along its Main Line, which extended west of Philadelphia through parts of Montgomery, Delaware, and Chester Counties, and spurred similar suburban development in Chestnut Hill. Developers of new suburbs also sought to appeal to the middle class, and the railroads offered incentives (such as free or discounted tickets) to encourage middle-class families to build houses along their lines. The Pennsylvania Railroad’s activity along its Main Line inspired the president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad to develop a similar but more affordable planned suburb for the middle class, Ridley Park, simultaneously with the opening of a new line in 1870 through southeast Delaware County between Philadelphia and Chester. In response to the availability of rail service, Sharon Hill and Norwood also developed along the line. A new line of the Pennsylvania Railroad running from Philadelphia to Norristown and Reading, beginning in 1884, enticed real estate developers to buy up farmland to create the middle-class suburb of Cynwyd (formerly known as Academyville). Along the Main Line, during the 1880s the co-owners of the Philadelphia Public Ledger, George W. Childs (1829-94) and banker A.J. Drexel (1826-1893), developed the planned suburban community of Wayne. In South Jersey, beginning in 1885 local landholders near the Camden and Atlantic Railroad line sold building lots to create the new suburb of Collingswood. Around the same time, local entrepreneurs began to convert farmland into the new suburb of Haddon Heights and persuaded the Reading Railroad, owner of the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway, to establish a station to serve the community.

In the new railroad suburbs, buyers found large single-family and semidetached homes with expansive porches and yards, a distinctly different environment from Philadelphia’s row houses. Making these railroad suburbs attractive to these residents required not only countryside ambiance but also more infrastructure of the type available in the city, such as water systems and paved streets. The Pennsylvania Railroad acknowledged this in a 1916 brochure when it touted “the charm of this suburban life, with its pure air, pure water and healthful surroundings, combined with the educational advantages provided, churches, stores and excellent transit facilities to and from the city, is manifest.” Despite developers’ appeals to the middle and upper classes, however, the railroad suburbs were never solely the domain of the region’s wealthiest residents. Most evolved around or within existing communities with their own people and histories, and even the most luxurious suburban estates required a network of support from local businesses and service workers who lived close to the railroad stations in row houses or other modest homes. Starting in the 1890s, electrified streetcar lines also brought more class diversity to some of the same suburbs that had originated along the rail lines, including Chestnut Hill in Philadelphia and Merchantville and Collingswood in New Jersey. Transit fares held steady while working-class incomes rose, making more distant places affordable to a wider range of residents.

The Main Line Corridor

The Bryn Mawr Hotel, constructed in 1872 and rebuilt in 1890, echoed the atmosphere of the elite seaside resort town of Cape May, New Jersey. Developers used community centerpieces like the hotel and new Welsh names to entice prospective buyers to villages along the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad. (Wikimedia Commons)

The Pennsylvania Railroad’s role in developing Philadelphia’s western suburbs originated from its purchase of farmland during the 1860s and 1870s in order to straighten the route of its Main Line between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. With its expanded holdings within commuting distance of Philadelphia, the railroad developed a corridor of privilege from existing villages and the surrounding countryside. To increase the area’s appeal, the company gave Welsh and Scottish place names to towns that did not already have them: Athensville became Ardmore, for example, and Humphreysville became Bryn Mawr. To give prospective buyers an opportunity to become acquainted with the area, the railroad took its cue from the resort ambiance of Cape May, New Jersey, and built the Bryn Mawr Hotel (opened in 1872, rebuilt in 1890 and later home to the Baldwin School). Railroad executives led the way by building estate homes. Alexander Cassatt (1839-1906), later the Pennsylvania Railroad’s president, had a city residence on Rittenhouse Square, but in 1872 he began building Cheswold, a mansion set on fifty-four acres in Haverford. Leaders of Philadelphia business and industry followed, including department store partner Isaac Clothier (1837-1921), who built a castle called Ballytore in Wynnewood in 1885. Collectively, the communities and estates that developed around Pennsylvania Railroad stations from Overbrook west to Paoli became “the Main Line,” a name that became synonymous with upper-class living despite the continuing presence of other local residents as well as the businesses and domestic workers necessary to support a gracious lifestyle. Many of the massive estates later became home to religious orders, schools, or other institutions.

In Northwest Philadelphia, completion of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Chestnut Hill Branch in the early 1880s set off a new wave of suburban development west of Germantown Avenue. Henry Houston (1820-95), a member of the railroad’s board of directors with extensive land holdings in Northwest Philadelphia and adjacent Montgomery County, proposed the new rail line and then followed the pattern of the Main Line by beckoning elite residents to Chestnut Hill with amenities such as the Wissahickon Inn (1883, later the Chestnut Hill Academy), the Philadelphia Cricket Club (1883), and another Protestant Episcopal Church, St. Martin-in-the-Fields (1888). In his Wissahickon Heights development (later renamed St. Martin’s), he made homes available by lease. Houston’s son-in-law George Woodward (1863-1952) continued the family tradition and Chestnut Hill’s suburban evolution in the early twentieth century with picturesque developments such as French Village (1913), Linden Court (1915), and English Village (1925). Between Chestnut Hill and Germantown, in Mount Airy, the Drexel Company built the planned suburb of Pelham between 1895 and 1910.

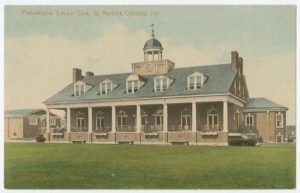

Construction of the Philadelphia Cricket Club in 1883 helped cement Chestnut Hill’s image as an exclusive retreat for the wealthy. By this time, both the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads operated competing lines from Center City to the area. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

In the golden age of railroad suburbs, from the 1880s through the 1910s, more than one thousand daily trains served hundreds of stations in and around Philadelphia. The combination of railroad and streetcar suburbs brought population growth to Philadelphia’s suburbs. The population of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, doubled between 1870 and 1920 while Delaware County, Pennsylvania, and Camden County, New Jersey, quadrupled during the same period. Most early growth took place within about an eight-mile radius of the city, because of both travel time and the distance-based railroad fares. Bedroom communities within this range included Bala, Cynwyd, Darby, Jenkintown, Lansdowne, and Narberth in Pennsylvania; and Audubon, Bellmawr, Collingswood, Haddon Heights, Haddonfield, Magnolia, Runnemede, Westmount, and Westville in New Jersey.

Autos Begin to Erode Rail Demand

By the 1920s, automobiles and buses came into the suburban transportation mix and railroad suburbs, although still located on train lines, no longer depended on the rails to link them to the city and neighboring communities. In New Jersey, the 1926 opening of the Delaware River Bridge (later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge) also hastened the shift from rail to automobile commuting. As passengers left the trains, the railroads eliminated or cut back service on many lines, although the Pennsylvania and Reading railroads invested in electric trains and often increased services between 1915 and 1933. After World War II, as automobile ownership and suburban bus service increased, and by the 1960s, the once-dominant railroads wanted to discontinue their money-losing commuter trains. In Pennsylvania, the City of Philadelphia and then the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) intervened in the 1950s and 1960s, and by 1983, SEPTA had taken over the remaining trains. For the New Jersey suburbs, the Port Authority Transit Corporation (PATCO) between Philadelphia and Lindenwold took the place of earlier rail systems in 1969. New Jersey Transit’s River Line began operating between Camden and Trenton in 2004. In the automobile age, some railroad suburbs retained their appeal as fashionable enclaves while others transitioned into neighborhoods of large houses divided into cheap apartments.

In the early-twenty-first century, although most people living in Philadelphia’s railroad suburbs did not use the trains to go to work, the old commuter lines still affected the social geography of the region because the road system largely followed those lines. With the exception of a handful of edge cities like King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, much of Philadelphia’s suburban development followed the old railroad lines. In 2017, SEPTA and PATCO trains still carried more than 156,000 daily riders, including not only suburban dwellers but also working-class and lower-middle-class reverse commuters traveling to jobs in the suburbs. Along the tracks, railroad stations and homes built by the enterprising developers of the nineteenth century survived as visible reminders of the origins of the railroad suburbs.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor-in-Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. John Hepp is Professor of History and co-chair of the Division of Global Cultures at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. He teaches urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the middle classes in the period 1800 to 1940.