In March of 1681, King Charles II of England (1630-85) granted William Penn (1644-1718), gentleman and Quaker, the charter for a proprietary colony on the North American continent. Although both English colonial policy and the organization of the Society of Friends, known as Quakers, were works in progress between the years 1682 and 1701, in many ways the pattern of scattered farms and religious tolerance that Pennsylvania developed in those early years became a model for an American way of life.

William Penn received a generous land grant from King Charles II of England to create a Quaker settlement in North America. The grant settled an old debt owed by the king to Penn’s father. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Penn’s grant settled an old debt owed by the king to Penn’s father, Admiral William Penn (1621-70). The king’s charter to Penn set the northern border of Pennsylvania at 42 degrees north latitude (the border of New York), and the eastern limit at the Delaware River (the boundary with New Jersey), while the western limit was undefined. Named for the admiral as well as for the woodland it encompassed (Penn’s woods), the new grant differed in form and substance from those offered to proprietors of other colonies. Under the proprietary system, the grantee obtained a charter from the king and established the colony at his own risk. The Crown looked on it as a feudal estate, a grant equivalent to independent sovereignty limited only by loyalty to the king. Proprietors could grant titles, had sole authority to initiate laws, levy taxes, coin money, regulate commerce, appoint provincial officials, administer justice, grant pardons, make war, erect manors, and control the land and waterways.

By the time Penn received his “true and absolute proprietary of Pennsylvania,” the powers given to proprietors had become much more limited. He still had complete control of granting land: in the common parlance of the time period under 100 acres constituted a farm, between 100 and 1,000 acres a plantation, and over 1,000 acres a manor. Those holding larger parcels could, in turn, sell or rent them as smaller holdings. The proprietor no longer had the right to grant titles of nobility, however, and he had to submit provincial laws to the king for approval, acknowledge the right of Parliament to tax the colony, maintain a provincial agent in London, and present all Pennsylvania laws to the “freemen” or to “their delegates” for approval. Most disappointing to Penn was an added clause that gave the established Church of England’s Bishop of London the right to appoint an Anglican minister in Pennsylvania. Penn had recruited settlers, largely Quakers, but also Mennonites, and other pietists, from widely dispersed parts of Britain and Europe and saw this clause as making them “dissenters in [their] own Countrey.” However, since his first law code guaranteed religious freedom from the legal penalties and punishments that inhibited the practice of Quakerism and other dissenting Christian groups in England, it was still possible to promote Pennsylvania as a religious refuge for the persecuted.

In July 1681, Penn issued his first conditions or “concessions” to “adventurers and purchasers” that laid out specifications for a great city on a river, provided for road surveys, related grants of city land to country manors, and set up townships. Penn’s blueprint for Pennsylvania was unique among colonial frames of government by containing several provisions requiring that “natives” be treated equally with settlers both economically and legally and that “no man shall. . . in word, or deed, affront, or wrong any Indian.”

The First Frame of Government

Penn followed up the concessions document in May 1682 with the first Frame of Government, which laid out the form and shape of governance in the new colony. The government itself was to consist of the governor, a Provincial Council, and a General Assembly chosen by the freemen who were defined as those who were resident in the province, were free of servitude, owned and cultivated part of their land, and paid a tax to the government.

The traditional story of William Penn’s peaceful treaty with the Lenape is depicted in this Currier & Ives lithograph based on the painting Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, by Benjamin West. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

Twenty-three ships bearing settlers arrived in the new colony between December 1681 and December 1682. The Welcome, William Penn aboard, landed on October 28, 1682. Within two years, fifty ships had arrived in Pennsylvania carrying 600 investors and 4,000 settlers. Penn and his colonists entered a land that was populated by Native Americans and European settlers who provided food and shelter to the newcomers, allowing the new colony to avoid the “starving time” that had been the fate of other earlier colonies to its north and south. Including the Europeans who settled West New Jersey in the 1670s, there were about 2,500 Lenape Indians and 3,000 Europeans on both sides of the Delaware River when Penn’s colonists arrived.

The inhabitants were diverse, including the Lenapes from whom Penn purchased land on the west bank of the river. The European inhabitants included the Dutch, who had established a trading post in the area in 1624, and the Swedes and Finns who created the first permanent settlement of New Sweden in 1638. Most of these settlers lived in the area from what was later Philadelphia to New Castle, Delaware. The Dutch conquered New Sweden in 1655 and then, following England’s victory over the Dutch in 1664, King Charles’s brother, James, Duke of York (1633-1701) took ownership of the west bank of the Delaware River.

In 1682, Penn divided the land along the Delaware River into the counties of Chester, Philadelphia, and Bucks, appointing colonists to serve on each county court and administer local government. To allow Pennsylvania an outlet to the sea, in the same year Penn leased from the Duke of York the land south of Chester County on the western shore of the Delaware Bay, setting the border of the “three lower counties” (later the state of Delaware) twelve miles north of New Castle. The charter for Pennsylvania and the lease for the three lower counties remained separate entities, however, requiring agreement to laws by a single assembly that met alternately at Philadelphia and New Castle. By 1704, the inconvenience of this arrangement led to a mutual agreement to set up distinct assemblies and pass laws separately, although they continued to share a governor. The border between Pennsylvania and Delaware was not actually established until the mid-eighteenth century, with the drawing of the Mason-Dixon line, which also settled the boundary with Maryland.

“Holy Experiment” Did Not Materialize

Penn’s hope for a “Holy Experiment”—where Pennsylvanians did well economically while doing good morally and religiously—failed to materialize. Landed gentleman investors did not, in general, emigrate, and their investments went badly. The Society of Free Traders was bankrupt within a few years. Penn, himself, never achieved the profits he expected. Although he lived until 1718, he only passed four years in Pennsylvania (1682-84 and 1699-1701). He was bedeviled by personal and financial problems and had to remain in England to attempt to resolve them. He actually spent time in debtors prison.

Early arrivals who prospered were largely farmers from northwestern England, an area of scattered farms, along with urban artisans and workmen, many of them from Germany and Holland. Settlers also came from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and London and its environs. By 1690, the population of the colony numbered about 11,500, that of the principal city, Philadelphia, about 2,000. Ten years later, the colony had close to 18,000 inhabitants, and Philadelphia over 3,000. The Society of Friends was never established as the official religion of the colony and Quakers were always a minority, although their influence was predominant in both the government and the early society.

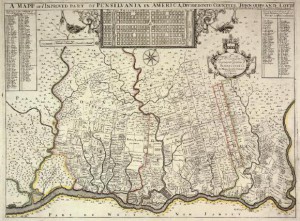

Thomas Holme’s 1687 map of Pennsylvania shows the tracts of the First Purchasers. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

While religion continued to motivate many settlers, many more were drawn by the rich farmland and its availability. The desire for wealth prompted importation of bound European servants and enslaved Africans. Penn had envisioned a colony of townships, where farms would produce the crops and livestock needed to fuel local centers of government, religion, industry, and trade. Instead, the Thomas Holme 1687 map of Pennsylvania indicates that almost from the beginning scattered farmsteads became the pattern of settlement for the three counties. Lumbering, grist mills to produce flour, and iron-mining operations as well as small manufactories for textiles, paper, and printing dotted the countryside from the 1690s. By 1701, however, Philadelphia had become the focus of trade, manufacture and civic life, exhibiting most of the attributes of an urban complex and draining the vitality out of potential township centers.

Welsh and German settlers, receiving large grants just outside Philadelphia, made the most determined efforts to maintain their identity. The Welsh Quakers in the Welsh Tract (1684) stood out for their attempts to maintain their own communities with the rights to hold contiguous property, limit the activities of anyone within their boundaries, and govern themselves in their old ways. Within the year, however, assimilation with English Quaker and Anglican settlers overwhelmed the Welsh and the tract survived mainly in Welsh names such as Bala Cynwyd and Bryn Mawr.

Germantown Was Unique

The house depicted in this early twentieth-century postcard was built on the site of the home of Thones Kunders, where the Germantown Society of Friends held its first meeting and where the first formal protest against slavery in North America was written.(Library Company of Philadelphia)

The situation of Germantown was unique in the founding years of Pennsylvania. Through some confusion, Penn granted the same territory to both a group of Dutch Quakers and the German-based Frankfort Land Company whose legal agent was Francis Daniel Pastorius (1651-1720). They arrived at the same time in 1683. As Pastorius was the only member of the company to immigrate, he became, de facto, the leader of the Dutch group, apportioning the land and heading the government. By 1684, the territory acquired its name as it was flooded with German immigrants of many religious sects. The craft occupations of the inhabitants and the distribution of Germantown’s land in small lots strung along a highway leading from Philadelphia to the hinterlands created a miniature urban center. It was chartered as a borough, but failure of the settlers to perform its governmental functions led to loss of that status in 1707. The Quaker meeting retained many of its German beliefs, leading to a protest against slavery in 1688 and a split within the meeting itself over the Keithian controversy in the 1690s.

Ever since the first “Frame of Government and Laws Agreed Upon in England” in 1682, factions of settlers were dissatisfied with its terms, and it was superseded or amended several times—in 1683,1684, and 1691. The colony was taken away from Penn in 1693 on suspicion of treasonable association with James II, but returned to him in 1695, initiating yet another charter in 1696.

William Penn rented this home on the 100 block of Second Street during his second stay in Pennsylvania from 1699 to 1701. It was here that he wrote the final Charter of Privileges. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

The final Charter of Privileges was granted in 1701 since the older frames had all been found “not so suitable to the Present circumstances of the Inhabitants,” and remained in force until the American Revolution. Each frame had gradually increased the powers of the elected assembly and it now received more privileges than any other legislative body in the English colonies, undoubtedly more than Penn, himself, had originally intended. A unicameral legislature with its Assembly elected annually could initiate legislation and conduct its own affairs, but the proprietor or his governor retained the right to veto legislation.

Most significantly, the first clause of the Charter of Privileges reiterated Pennsylvania’s commitment to religious liberty—freedom of worship to all who “acknowledge one almighty God” without attending or belonging to a religious body, and the ability to serve in office by all who believed in Jesus Christ and were willing to affirm, if not swear, allegiance to the government. The affirmation was important to Quakers who refused to swear oaths. Along with Rhode Island and several other colonies, Pennsylvania was a pioneer of the separation of religion and government in the American colonies.

Stephanie Grauman Wolf is a senior fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania and author of As Various As Their Land: The Everyday Lives of Eighteenth-Century Americans.